For many, holidays are a time for introspection and thanksgiving. Each year, around this time, I reflect on the important people in my life. This is my story. I could have grown up a motherless child, but the man up there was looking out for me.

Maybe my dad didn’t see it coming. I imagine my mother yelling, her brown eyes closing, cheeks tensing up as she slipped away into unconsciousness. Broken glass everywhere. Dead. He must have thought she was dead. He must have screamed her name and tried to unbuckle her seat. He must have panicked until he remembered me. Rana was back there in the car seat. My head swelled as the seconds passed. Did he hear me whimper?

There is one early memory that stands out to me. A picture.Pre- accident. Living room. My mom’s kneeling on the carpet floor. Her nose at my sister’s cheek and her arms around me. She is smiling widely. I am looking at the camera. Dad, who was taking the picture, was probably making one of his infamous quirky faces. How happy she was, my mom. This was before the rainy night. The night that made my mom refuse to drive in the rain for many years to come. It wasn’t until many years later did she realize she couldn’t be scared anymore.

There’s another picture that jitters my memory. My dad holding me. Now, we are in a hospital. I don’t look like the baby from the first picture. There is a tube running from my nose to someplace I can’t quite see. My dad is smiling! He has a gap. The hospital crib with the tall metal sides and the breathing machines and all the other health paraphinilla don’t really matter. Maybe he was smiling because he was happy I was alive! Was I happy? I was sad to be in that cage and to be away from my mommy. Where was my mommy, daddy? The teddy bears on my hospital gown all seem blurry as I recall the picture in my head. My dad’s gap was so bright and his green jacket brought out the gold in his hair and the green in his eyes. He looked so young then.

The next picture is in the same hospital as the previous one. But now we are all together as a family. Naeema, Rana, Dad, and Sleeping Mommy. “Why is Mommy sleeping?” Naeema asks. After the accident, she had been staying with my Aunty Maureen, my mother’s older sister who lived in Montclair. She was the closest relative to us and my dad had to work, so someone had to watch Naeema. She probably couldn’t comprehend what it meant that her mother had been in a really bad accident. What type of accident? I wonder who answered her or what they told her. I wonder how she felt when she realized my mother would never be able to run with her again or take her for walks to the park. I don’t think she anticipated that “the cane” would be the object of our contempt for a while.

Back to the hospital room and that picture. I wonder if this was the moment where I realized my life had changed. I was only a little past one year, but I knew my mom was sleeping. I was smiling in this picture though. Maybe this was the first time I had seen my mother since the accident. I must have been happy for her to wake. But she never woke. I don’t know what happened after that picture was taken. Maybe my smiles turned to tears as I was passed around the room to an armful of well-wishing visitors. No one could stop my tears. My mother always told me I was a miserable baby. I’d cry for no reason.

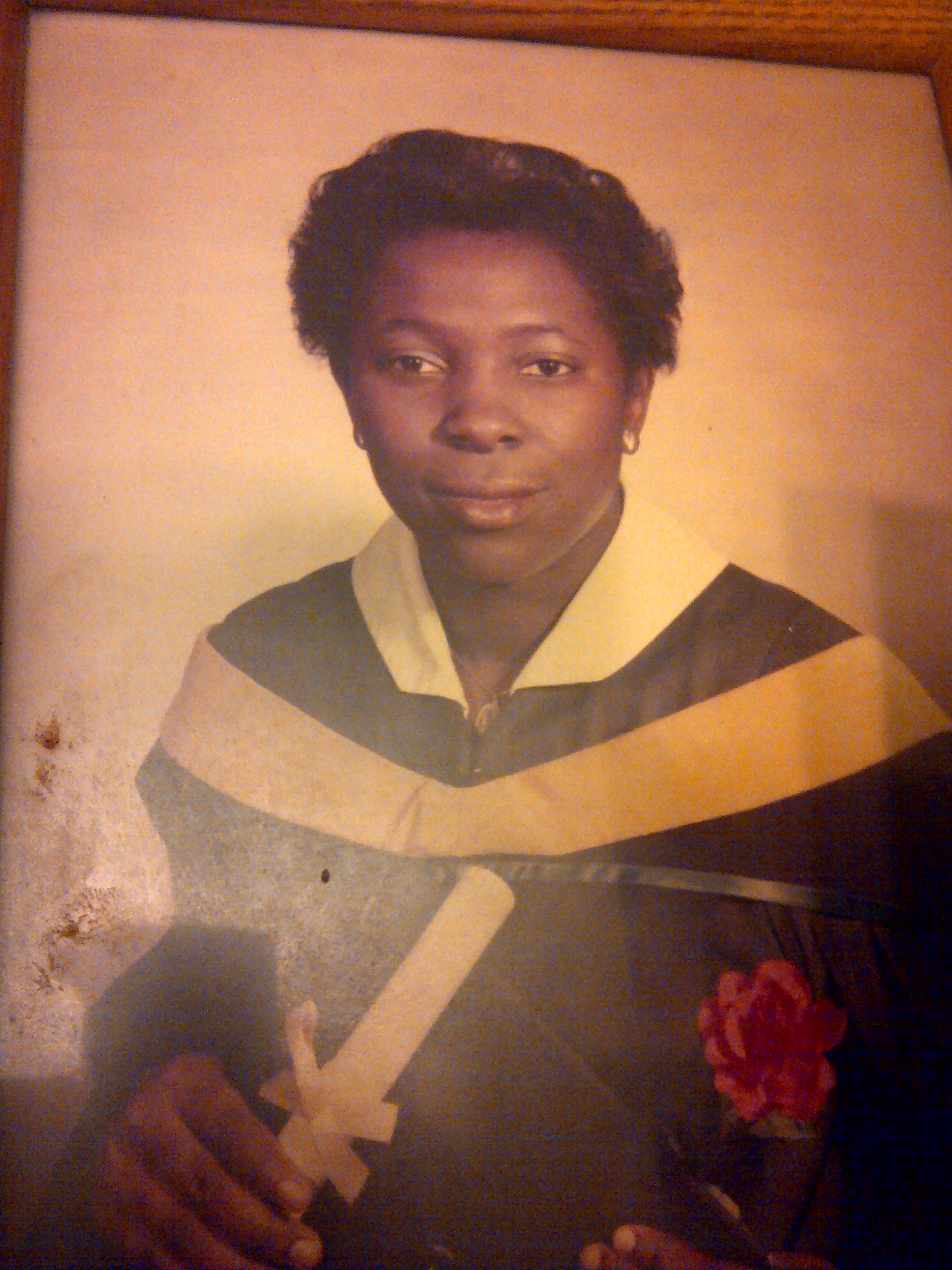

And then the final picture. Post- coma. Post rehab? Post Traumatic Brain Injury. We are in my house now. My mom is no longer smiling. She is holding my sister despondently and I am leaning on her knee. Waiting for a touch. Her chin is slightly tilted upwards. Her hair pulled back, but I can’t see her teeth. There is no smile. A hospital band is on her left arm. My swelling has gone down. I look like a normal baby. Perhaps I had relearned to walk. Or maybe I was holding on to her for stability. The picture was taken in my living room. My sister is smiling. She has on a school uniform. She is leaning on my mother’s knee. The beads from her hair reflect the light ominously. I don’t think my father was smiling in this picture. Maybe he was. Maybe he was fighting back tears.

I wondered if she was able to pick me up and carry me around the house as most mothers do when their child is of age. I never really asked her and when I do, she never responds. To her, I imagine, the reasoning is somewhere along the lines: If I could I would have but I couldn’t so why ask me to hurt me. I never knew you before then, mom. I only have pictures. She never responds.

Though I hadn’t suffered as serious injuries as my mother did, my fractured skull was still of great concern. It was something that had to be protected, documented and monitored, but never really talked about. It all seems foggy now, but I remember going to the hospital for x-rays. I was very young and someone had to lift me onto the x-ray table. The mat that the nurses used to cover my body to protect me from the radiator weighed me down. I remember making up little games to pass the time. I’d hold my breath and count and see how long it would take until I heard the beep of the machine as they moved the x-ray to different parts of my body. I imagine they weren’t only taking pictures of my head, but of my whole body. Was I growing right? What was wrong with me? I didn’t get much answers, but I know that the hospital visits were routine and serious. When I got older, my mother took me for checkups at larger facilities, or so they seemed. My memories of the clinic place me inside a doctor’s office. Yellow waiting room with brown seats. The hallways were longer. The smell was colder. The CAT-SCAN was the best way for the doctors to assess the remnants of my injury in my early adolescent age. I remember being told to keep still as they slid my body into an open white tomb. By being still, I thought this meant that I shouldn’t breathe. After holding my breath for many seconds, I finally asked if I could breathe. The nurses laughed as they fidgeted with the CATSCAN from another corner of the room.

It was lonely inside the tomb, and I was happy when it was finally over. This was something I didn’t like at all.

I don’t think I ever had to get anymore CATSCANs, but my next memories of skull checkups place me at an entirely different setting. Mom told me that because I was getting older, I had to go see a specialist. The specialist would be able to answer any of my questions and help document my progress. Up until this point, I wasn’t quite sure what having a fractured skull actually meant. The waiting room for these checkups was much different. Warmer. Colorful. Toys. I talked to the doctor. He asked me questions that I thought were quite useless. “Does your head ever hurt, Rana?” “Does your head hurt when I do this?” “Do you ever feel pressure?” I answered him the best that I could. I’m sure I told him that my head hurt sometimes especially when I touched it a certain way. I told him that I didn’t want to have lumps in my head and that I wanted him to make them go away . Please. The doctor showed me pictures of my skull. I tried to make sense of it all, but at that age, it just looked like pictures and the doctor visits were only places that my mom took me to.

To me, my mother symbolized a list of could nots. She couldn’t sing. She couldn’t whisper. She couldn’t run. She couldn’t walk fast. She couldn’t jump on the bed and pillow fight with us. She couldn’t catch me if I ran away. She couldn’t use her right hand to write pretty cursive like I was learning in school. She couldn’t chop carrots fast. She couldn’t walk long distances without getting tired. She couldn’t walk around the amusement park without needing a wheelchair. She couldn’t go anywhere without her cane.

I hated the cane and everything that it stood for. The cane was a crutch for her happiness, but an accelerator for my unhappiness. Using the cane for my mother, I presumed, brought her joy. It helped her keep her balance. It helped alleviate the pressure she sometimes felt on her right leg, the one that always swelled and gave her lots of problems. But for me, it was a source of embarrassment. It was like placing a big sign on her head that read “Hey, I’m Rose and I have a disability. Rana is my daughter. My daughter has a mother with a disability” on her head. I don’t know what I was more embarrassed of. The cane or what other people saw when they saw the cane.

As a young child, I tried to teach my mother to walk fast. I thought that she simply didn’t try hard enough. I had spent a whole summer teaching my pet Cockatiel, Sunny, how to run. I made an obstacle course of pillows on my living room floor and used a blanket to help push him through the obstacle course. The faster I ran, the faster Sunny ran. I thought this same logic would work on my mother. Sometimes when holding her hand as we walked through a store, I’d suddenly increase my pace. She kept up with me for a few footsteps. She was walking normally, I thought in my mind. She could actually do it, she just had to practice. My mother was always the one to tell me that I could do something if I kept practicing. My joy never lasted, because after a few moments, my mother would realize what was happening and start to panic. I’m going to fall! I’d let go and sulk off. I failed. I couldn’t teach my mother to run. She wasn’t a bird. She’d always need her cane and I never quite got over that as a kid.

It was hard for me to deal with the aftermath of what the accident did to my mother. Most of the confusion has been because I didn’t understand how much her life changed in that split second. It’s funny how life works its magic. How the future is told at the very precise second the moment is happening. Some people bounce forward while others take lifetime steps back. How you can go from being a fully functioning adult to not knowing how to speak, how to write, or how to read. She was in the last semester of nursing school at the time. She had her family, a loving husband, and her dreams to look forward to. Life seemed good until the accident. Then life became shaped by it.

The “accident” is what everyone who knows me and knows of it calls it to this day. It was the day that changed my life. It shaped how the rest of my life would play out. It was the first domino in the long chain of dominos on the table called life. Sometimes I wonder how much of an “accident” it was. Is accident even really the right word? I’ve grown to question the idea of inevitability and destiny. Maybe the timing of two cars colliding was more than a “could have been avoided” moment. Maybe tragedies are part of a grander destiny.

Is the first domino that falls the most important, or is it the second, or third?

Sometimes I don’t tell my mother I love her enough. Over the years, she’s been a great symbol of strength, loyalty, and determination. After months of rehab and years of recovery, she’s accomplished things the doctors said she would never do: learning how to write again, to read again, to walk again. Her life, in many ways, was snatched by a rainy night. She snatched it back. She did.

I love you, mom. For you, I am forever thankful. For you, I am eternally grateful.

Latest posts by Rana Campbell (see all)

- How To Create Possibility For Your Life Despite The Odds - December 10, 2017

- From Stockbroker to Beauty Entrepreneur: How Melissa Butler Launched The Lip Bar From Her Kitchen & Succeeded - December 6, 2017

- How Choreographer Aliya Janell Created A Viral Brand Dance Brand And Gained Over 700k New Followers In Less Than 1 Year - November 22, 2017

Tags: advice, documentary, life changer, love, mom, motherly love, thanksgiving

[…] While we’ve all had bouts with other women that may not have gone too well, friendships with other women can be highly rewarding and inspiring. There are so many women in my life who have had such an incredible impact on me and have played a important role in my development as a women in many aspects of my personal life, emotional well-being, and career development. My mom, one of the strongest women I know, is my shining example of the strength of a woman and all that can be learned from having one by your side. […]