Here’s a link to an opinion piece I wrote about my experiences volunteering in Prison for Madame Noire.

Read the full text below:

I was 17 when I saw a gun up close for the first time. I was at the house of a childhood friend. He was a gang member and had been getting more and more involved in the street life.

“Wanna see something, Rana?” he asked.

He went into another room and rustled around and returned with a partially opened shoebox. Iron dimly sparkled from within.

“Is that what I think it is?” I questioned him. He looked at me blankly.

I was confused. I guess he really was getting “in deep” as he liked to tell me. I guess the life he was living was something I could never understand, a stark contrast to our innocent bike-riding, tag-playing childhood days.

Tears started to run down my face.

“Why you crying? Stop crying, Rana.”

But I couldn’t. The tears continued to fall. He put the iron back into the box and returned it to its hiding place.

Fast forward one year: I was a Freshman at Princeton. It was October. I had just received a call from an unknown number. “Hello?” I answered. “Hey Rana, it’s me.” I recognized the voice of my friend instantly. “How you been?…You like Princeton?” the conversation continued for a few minutes and ended with a simple “just checking on you… I’ll hit you up soon.”

But he didn’t. In fact, we didn’t speak for another three years. A few months after that phone call, my friend was sentenced to prison for illegal weapon possession charges.

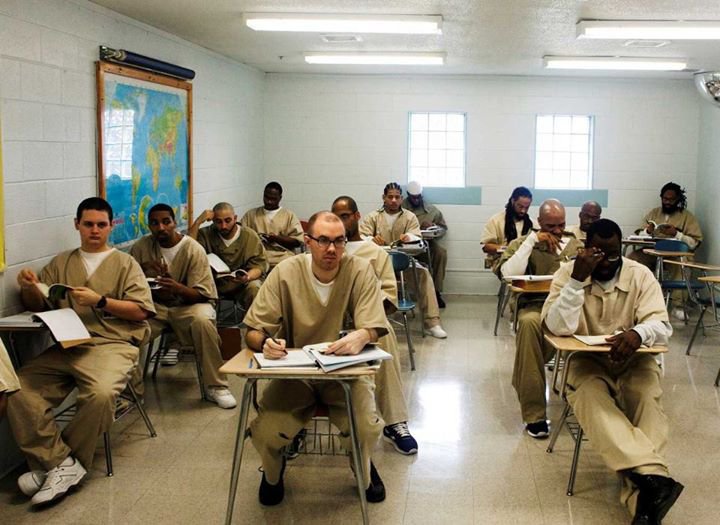

Around the same time, I started volunteering in prison with the Petey Greene Prisoner Assistance Program, a program that allows students to tutor young male inmates (aged 18-25) in local NJ state prisons getting their high school diplomas and GEDs. When I saw the flyer advertising the program, I knew I had to sign up. I knew I wanted to help.

See, I’m from Orange, a small neighborhood in New Jersey. Orange is an urban suburb of the infamous Newark, New Jersey and shares many of the town’s pitfalls such as crime, violence, and economic instability. At the age of 12, I was provided an opportunity that changed my life. The chance to attend a prestigious college preparatory school, Dwight Englewood, which was located about 20 miles from my house. For middle and high school, I was exposed to so many people and things I don’t think I would have ever experienced in Orange. The cultural and social capital I built and the connections and networks I made allowed me great opportunities. I became educated in the liberal arts way. I was prepared for success. Located in one of the richest counties in the United States, Dwight Englewood was paradise, a place where it was very easy to forget about “reality.”

But I had to go home every day. I went home to a neighborhood riddled with hopelessness. In my junior year of high school, a dear childhood friend of mine died. I was devastated. I remember going to his wake and not recognizing his face in the casket. I remember the swarms of his friends who proudly wore the insignia “G.I.P…” Grape in Peace. These individuals were paying homage to the same force that killed him. It sickened me.

I went home to a neighborhood where my best friends were getting a subpar, unchallenging educational experience. I went home to a neighborhood that was in utter social despair, both physically and spiritually. I had a sense of survivor’s guilt. At the same time, I felt like I had to change something.

To whom much is given, much is expected.

Volunteering in prison isn’t for everyone.. You’ve got to be mentally strong to endure what you will see and hear. To walk past lines of Black and Hispanic men in handcuffs looking anxiously at you, the only civilian female they’ve seen in months (or years?). To wait behind iron gates as correctional officers allow you access to the other side… to freedom.

Have you ever tried to help a 23 year old man do simple arithmetic? Ever sat down with a fresh-faced 19 year old who can barely read? Have you ever had someone ask you what’s the weather like outside? What’s the newest song? What does the front of the prison look like? Have you ever seen grown men living in conditions where they feel sub-human?

I volunteered in prison for more than just tutoring. During my three hours in prison each week, I tried to touch lives. I tried to give back hope to a lot of young men who might have never thought they could be something in life. Many of them had already sentenced themselves to a negative life trajectory. I realized how little rehabilitation was going on within supposed “rehabilitation facilities.” Wait, isn’t that what prison is supposedto be?

“What do you think you are going to do when you get out?”

“Same ish. Selling Drugs. Probably end right back in here.”

Once, during a writing class I was teaching, I mentioned the fact that I needed change to retrieve my personal items from the locker in the main entrance of the prison. One student responded,

“ I haven’t seen money in three years.”

“How old are you?”

“19.”

During another class I overhead an inmate telling his classmate that he missed his son who was “getting real big” the last time he saw him.

“My son is five! I’ve been locked up since he was born.”

“How old are you?”

“20.”

Stories like this can break your heart. Or, they can inspire you to keep doing the work. They can challenge you to think about a segment of the population that many people of color aren’t doing much about. In the United States alone, over 2.2 million people are currently serving time in prison or jail. Last year, 53.5 billion dollars alone was spent on financing the criminal justice system. While I do not believe every person in prison is innocent, it is common knowledge that discriminatory criminal justices policies are unfairly enacted in low- income minority communities, resulting in an overrepresentation of these populations within the system.

I went to prison knowing that I could make a difference. I knew that my story, my experience, my hopes could serve as an inspiration to someone who might have given up.

Rewind one year: My friend was released from prison. For a documentary filmmaking class project, I interviewed him and asked him to reflect on his past, present, and future aspirations. (Watch the interview here.) A year later, he’s on a road towards success and I’m proud to see that he’s moving past the rearrests, shootings, financial woes, family drama and fighting to become a better person. One that doesn’t end up back in prison.

So while we all love entertainment, fashion, and beauty, it is time we start thinking about the larger issues. Incarceration hurts families, destroys neighborhoods, and worse of all, creates broken individuals. These individuals reenter society at some point in time. When are we, people of color, going to start making a ruckus about the issues that matter? Volunteering in prison allowed me to see these issues up close and personal. Not everyone has that opportunity, or wants it, but just because you may not have a personal tie or care, mass incarceration can, will, or is affecting you in some way. Believe me.

What are your thoughts on mass incarceration? What issues do we need to start discussing more when it comes to criminal justice? Share your thoughts.

If you’d like to read my senior thesis “Perspectives on Policing in Orange, New Jersey: Views from Law Enforcement Officials, Police Chaplains, and Community Residents”, or if you want to see the full Lost Boy documentary, email me rana@ranacampbell.com

Latest posts by Rana Campbell (see all)

- How To Create Possibility For Your Life Despite The Odds - December 10, 2017

- From Stockbroker to Beauty Entrepreneur: How Melissa Butler Launched The Lip Bar From Her Kitchen & Succeeded - December 6, 2017

- How Choreographer Aliya Janell Created A Viral Brand Dance Brand And Gained Over 700k New Followers In Less Than 1 Year - November 22, 2017

Tags: blacks in prison, inner city, princeton, volunteering in prison

So proud of you,you will always accomplish great things,enjoy all of your work,keep in touch!! Mrs.Ogburn

I watched your video interview w/’LB’ and his testimony about himself shows he has broken the law in serious ways, harming others, not to mention himself. Maybe his incarceration prevented him from more serious crime, such as murder. I agree that there is disproportionate minority residency in U.S. prisons. To answer the question why seems difficult to me, but I haven’t a doubt that discriminatory injustice is involved. There are certainly other issues to be considered as well, the insidious effects of racism in U.S. society that has been going on for centuries, family problems within the black community, how an individual views and values himself, gangs, drugs, etc., etc. The answer, I guess, would be complicated, Rana. That so many young black men are in jail, is it a way of the majority white population suppressing a minority group (I happen to be white) for surreptitious, racist, reasons? I myself broke the law as a young man, in serious ways, and 1 time, I spent a night in jail (I can give you the details privately, if you should be interested).

Anyway, you’ve touched on something important, something that should be changed, if possible. [I was referred to your blog by your post on Fb, ‘Orange – Who’s from or lived in Orange, New Jersey?’ You are a great writer, clear & logical. I’ve lived in Orange since 1960!]

The above post is from me, paulyr. I didn’t mean to be anonymous.

Hi Pauly! Thank you so much for such a thoughtful response. Indeed, you brought up alot of great points. This is a conversation that I wished more in the Orange (and surrounding communities) would have about the issues that so present, but yet, ever ignored. If you would ever like to talk more, let me know!